Archived version of Prof. Dr. Bernhard-Michael Mayer’s blog post.

Originally published on 02.10.2014

In this post, I will comment on the Position Statement of the Forum of International Respiratory Societies (FIRS) on electronic cigarettes, published in the distinguished American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine 1. In my opinion, this statement is extremely biased and full of unjustified assertions. The suggested ban and/or tough restriction of electronic cigarettes is unethical and contradicts the Hippocratic oath as the switch from tobacco products to electronic cigarettes could save millions of lives.

Recently this statement was supported in a slightly modified and condensed form in an Editorial published in Respirology 2. A brief Correspondence I had submitted for publication in that journal was rejected by the Editor (co-author on the paper), saying that the answers to all of the questions raised in my Correspondence could be found in the above mentioned Position Statement. Since I could not find the promised answers there, I decided to publish my view in this blog. Below you find a point-bypoint discussion of the suggestions and concerns raised by the FIRS in their paper.

Discussion of the concerns and suggestions raised by the FIRS

There is concern that the use of electronic cigarettes is growing rapidly, especially among young people and women. Their acceptance may be attributed in part to the perception created by marketing and the popular press that they are safe.

It should be obvious to anybody equipped with a minimum of common sense that the vapor of e-liquids containing only propylene glycol, glycerol, and food flavorings, in addition to nicotine, is less harmful than tobacco smoke with several thousand potentially toxic compounds, including carbon monoxide, tar and more than 60 established carcinogens. Therefore, the rapidly growing use of electronic cigarettes is not a matter of concern but a blessing. At least for someone seriously interested in tobacco harm reduction.

The authors may wish to consider that the acceptance of these products is not a consequence of marketing or media reports but simply due to the fact that they allow smokers to perpetuate their habit of nicotine consumption in the absence of significant harm.

The health risk of electronic cigarettes has not been adequately studied.

This statement is meaningless in the absence of a clear proposition of a particular health risk that should be studied and what will be considered as being “adequate”. Normal use of these products by millions of consumers in the past five years has not caused documented cases of serious poisoning, indicating that electronic cigarettes are not terribly toxic. Moreover, there are numerous studies showing that electronic cigarettes are less harmful than conventional cigarettes with respect to various physiological parameters and functions 3 4 5 6 7 8 9.

The addictive power of nicotine and its untoward effects should not be underestimated.

There is general agreement that nicotine is not particularly addictive in the absence of other tobacco ingredients, in particular monoamine oxidase inhibitors 10 11 12. It has been shown that nicotine does not cause dependence of nonsmokers 13. It may maintain addiction of former smokers, but in the absence of significant damage to health this is no reason for concern.

At normal dosage, nicotine is a relatively benign drug that does not cause considerable adverse effects. As stated in the consumer information to the FDA-approved group of nicotine containing products termed nicorette® (http://www.nicorette.ca/know-the-facts/truths-about-nicotine) “nicotine is not cancerogenic and not the cause of other smoking-related diseases”. In an inconsistency that is hard to beat, the Respiratory Societies are warning against the health risk of nicotine in electronic cigarettes but recommend FDA-approved nicotine replacement therapy. It seems that common sense has been lost on the way.

The potential benefits of electronic nicotine delivery devices, including harm reduction and enhancing smoking cessation, have not been adequately studied.

The benefit of electronic cigarettes in terms of harm reduction is obvious and well documented (see above). They are used as alternative sources of nicotine consumption and not for smoking cessation. There is no reason to study the efficacy of a consumer product in clinical trials.

Potential benefits to an individual smoker should be weighed against harm to the population of increased social acceptability of smoking and use of nicotine.

The argument would only be valid if free availability of electronic cigarettes caused increased smoking prevalence in the population. However, these products are almost exclusively used by former smokers as an alternative to tobacco products, and the gateway hypothesis has been refuted unequivocally in recent studies 14 15. The use of nicotine in the absence of tobacco is not particularly hazardous. Health organizations and medical societies need not be concerned about social acceptability of a behavior that is doing no harm. They are recommended quitting their ideological believe systems.

Health and safety claims regarding electronic nicotine delivery devices should be subject to evidentiary review.

No serious electronic cigarette retailer makes any health claims. With respect to safety, one wonders whether the authors request the same evaluation of related consumer products such as alcoholic beverages or coffee.

Adverse health effects for third parties exposed to the emissions of electronic cigarettes cannot be excluded.

Correct, but meaningless. Absence of evidence is not evidence of absence. Therefore, adverse health effects of the emissions of a fart can neither be excluded. In fact, it is not possible to exclude adverse health effects of anything. For further details, I refer to my post on the “Safety of electronic cigarettes and the Loch Ness Monster”.

Parties to World Health Organization Framework Convention on Tobacco Control should consider whether allowing use of electronic cigarettes is consistent with the requirements of the treaty.

I am not aware of anything that would be more consistent with the requirements of the FCTC than electronic cigarettes, which could pave the way for a tobacco-free world, a major goal of the WHO. However, the WHO has failed quitting its ideology of fighting against anything that looks like smoke or resembles smoking behavior, regardless of being harmful or not. I have discussed the ideological motivation of the WHO and related health organizations in the post “Pseudoscience in electronic cigarette policy”.

Electronic nicotine delivery devices should be restricted or banned, at least until more information about their safety is available.

Without precisely stating which kind of information is needed, this is a highly vague and unclear request. It appears that the Respiratory Societies advice smokers to continue inhaling burned tobacco because there might be a minor residual health risk of electronic cigarettes not yet recognized. Hard to believe that this is the honest opinion of lung specialists, who must have seen hundreds of smokers dying in agony from lung cancer.

In the absence of a ban, we recommend that devices that deliver nicotine be regulated as medicines. This includes the prohibition of their promotion for tobacco-use cessation and other health effects until there is strong evidence that establishes their benefits and lack of harm as is required by regulatory agencies for approval of other medicines.

In other words, it is the ultimate goal of the Respiratory Societies to ban electronic cigarettes, but they expect that the target will not be met. The second best solution is making the access to these products as difficult as possible. The hardest way is certainly regulation as medicinal products. Obligatory approval of electronic cigarettes as medicines would limit the range of products available on the market to virtually useless “cigalikes” and wipe out the highly successful second- and third-generation devices. On the long run, this approach gives health authorities a good chance to

become free of the spirits they have never called up. In the past few years, European courts decided several times that electronic cigarettes cannot be regulated as medicinal products in the absence of health claims, and the European regulation of electronic cigarettes (TPD2) has adopted this view. It is not the aim of a consumer product do cure a disease.

If electronic nicotine delivery devices are not regulated as medicines, they should be regulated as tobacco products. This includes: (1) a ban on all advertising, promotion and sponsorship; (2) prohibition of displays in retail stores; (3) prohibition of sale to minors; (4) regulation of internet sales; (5) taxation at rates similar to combustible cigarettes; (6) prohibition of sales and refills with flavors that will appeal to children; (7) requirement that packaging and labeling include a list of all ingredients and the quantity of nicotine; (8) placement of appropriate warning labels, the same as is required for tobacco products; and (9) prohibition of their use in public places, workplaces, and on public transportation.

Again, great efforts are being made to limit availability of electronic cigarettes as much as possible. What is the reason to treat these harmless products the same way as potentially deadly tobacco products? Where is the evidence for “appeal to children”? What is the justification for taxation at rates similar to combustible cigarettes? What is the rationale for the prohibition of their use in public places? Is there any evidence for health damage of exhaled propylene glycol vapor? There are two points in this list everybody will probably agree on: point (3), prohibition of sale to minors and point (7), the request for a list of all ingredients and the quantity of nicotine.

In the absence of a ban, manufacturers of electronic cigarettes should adhere to established consumer safety practices that list ingredients and produce consistent products with uniform concentrations and defined maximum doses of nicotine. They must safeguard against inadvertent poisonings, which includes child-proofing containers and other protections.

Manufacturers should of course meet the stated requirements. The efficacy of childproofing could be questioned. Strong alcoholic liquors, as well as cigarettes and many potentially hazardous household products, are sold without child-proofing. Nonetheless, overall the suggestions are acceptable.

Research supported by sources other than the tobacco or electronic cigarette industry should be performed to determine the impact of electronic nicotine delivery devices on health in a wide variety of settings.

The general public may applaud to this seemingly reasonable request. However, with this statement the authors implicitly accuse scientists of fraud and data manipulation if funded by industry. It should be distinguished between studies carried out by company employees themselves and industry-funded work performed by independent internationally recognized researchers.

The use and population effects of electronic nicotine delivery devices should be monitored.

Why? Is there any monitoring of the use of alcoholic beverages?

All information derived from this research should be conveyed to the public in a clear manner.

Fine.

Conclusion

The ignorance reflected by this list leaves me speechless. The suggestions are based on a consensus of international societies of lung specialists, experts knowing better about the hazards of smoking than anybody else does. Smoking is by far the greatest risk factor for the development of lung diseases with high mortality rates. Nevertheless, the esteemed Respiratory Societies arrived at a worldwide agreement on requesting a ban of products that have the potential to offer smokers an easy and virtually painless gateway out of tobacco consumption.

These products could be a success without precedent in the history of tobacco harm reduction, provided broad public advertisement and encouragement. In particular, the supportive advice from physicians would be extremely helpful because people trust in their knowledge and expertise. However, the experts unsettle their patients by unsubstantiated warnings of “unknown health risks”, “lack of long-term studies”, “unknown ingredients of liquids”, etc. To make it even worse, they are doing their best to wipe out these products all together.

Why are lung specialists stubbornly trying to keep their patients away from a product that is orders of magnitude less harmful to the lungs than combustible cigarettes? Do they really believe that the health risk of propylene glycol, glycerol or food flavorings exceeds the risk of tobacco smoke? Do they really believe in the efficacy of FDAapproved nicotine products? Do they really believe that the efficacy of varenicline (e.g. Champix ) outweighs its risks? Do they really believe that nicotine is highly toxic and addictive when freely available as a consumer product, but harmless and useful when sold as FDA-approved drug in pharmacies?

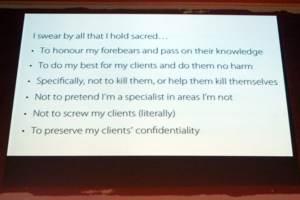

I don’t have the answers to these questions. However, I know that something is going terribly wrong in these medical societies. According to the Hippocratic oath, doctors are obliged to do no harm to the patients (primum nil nocere). The members of FIRS are requested reconsidering their suggestions in light of this famous vow.

Quellen

- Schraufnagel DE, Blasi F, Drummond MB, Lam DC, Latif E, Rosen MJ, Sansores R, Van Zyl-Smit R and Forum of International Respiratory Societies (2014) Electronic cigarettes. A position statement of the forum of international respiratory societies. Am J Resp Crit Care Med 190: 611-618.

- Lam DC, Nana A, Eastwood PR and (APSR) A-PSoR (2014) Electronic cigarettes:‘Vaping’ has unproven benefits and potential harm. Respirology 19: 945-947.

- Flouris AD, Poulianiti KP, Chorti MS, Jamurtas AZ, Kouretas D, Owolabi EO, Tzatzarakis MN, Tsatsakis AM and Koutedakis Y (2012) Acute effects of electronic and tobacco cigarette smoking on complete blood count. Food Chem Toxicol 50:

3600-3603. - Farsalinos K, Tsiapras D, Kyrzopoulos S and Voudris V (2013) Acute and chronic effects of smoking on myocardial function in healthy heavy smokers: A study of doppler flow, doppler tissue velocity, and two-dimensional speckle tracking echocardiography. Echocardiography 30: 285-292.

- Flouris AD, Chorti MS, Poulianiti KP, Jamurtas AZ, Kostikas K, Tzatzarakis MN, Wallace Hayes A, Tsatsaki AM and Koutedakis Y (2013) Acute impact of active and passive electronic cigarette smoking on serum cotinine and lung function. Inhal Toxicol 25: 91-101.

- van Staden SR, Groenewald M, Engelbrecht R, Becker PJ and Hazelhurst LT (2013) Carboxyhaemoglobin levels, health and lifestyle perceptions in smokers converting from tobacco cigarettes to electronic cigarettes. S Afr Med J 103: 865-868.

- Farsalinos KE, Tsiapras D, Kyrzopoulos S, Savvopoulou M and Voudris V (2014) Acute effects of using an electronic nicotine-delivery device (electronic cigarette) on myocardial function: Comparison with the effects of regular cigarettes. BMC Cardiovasc Disord 14.

- Polosa R, Morjaria J, Caponnetto P, Caruso M, Strano S, Battaglia E and Russo C(2014) Effect of smoking abstinence and reduction in asthmatic smokers switching to electronic cigarettes: Evidence for harm reversal. Int J Environ Res Public Health 11: 4965-4977.

- Polosa R, Morjaria JB, Caponnetto P, Campagna D, Russo C, Alamo A, Amaradio MD and Fisichella A (2014) Effectiveness and tolerability of electronic cigarette in real-life: A 24-month prospective observational study. Intern Emerg Med 9: 537-546.

- Villégier AS, Salomon L, Granon S, Changeux JP, Belluzzi JD, Leslie FM and Tassin JP (2006) Monoamine oxidase inhibitors allow locomotor and rewarding responses to nicotine. Neuropsychopharmacology 31: 1704-1713.

- Kapelewski CH, Vandenbergh DJ and Klein LC (2011) Effect of monoamine oxidase inhibition on rewarding effects of nicotine in rodents. Curr Drug Abuse Rev 4: 110-121.

- Frenk H and Dar R (2011) If the data contradict the theory, throw out the data: Nicotine addiction in the 2010 report of the Surgeon General. Harm Reduct J 8: 1477-7517-1478-1412.

- Gold M, Newhouse PA, Howard D and Kryscio RJ (2012) Nicotine treatment of mild cognitive impairment: a 6-month double-blind pilot clinical trial. Neurology 78: 91-101.

- Etter JF and Bullen C (2014) A longitudinal study of electronic cigarette users. Addict Behav 39: 491-494.

- Vardavas CI, Filippidis FT and Agaku IT (2014) Determinants and prevalence of ecigarette use throughout the European Union: A secondary analysis of 26 566 youth and adults from 27 Countries. Tob Control. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrolFiled Under: Blog Tagged With: cancer, COPD, ideology, lung specialists, pseudoscience, smoking 2013-051394. [Epub ahead of print]